When the human body becomes landscape: a conversation with Luna Cenere.

Luna Cenere

SP: You are a young dancer, born in 1987, but with already a lot of international experiences behind you. You graduated in contemporary dance from the National Promotion Body “Movimento Danza” in Naples at the age of 22 while also studying at the university, attending the Sociology faculty at the University Federico II of Naples. You started your dance studies simultaneously with your university studies. How did your interest in dance originate? How did you decide to pursue this professional path?

LC: I started dancing at the age of sixteen, immediately embarking on a journey in contemporary dance, aware of how I wanted and could express myself. Back then, dance was an interest I had to cultivate alongside school. However, being naturally curious, I always pursued my studies with pleasure and achieved good results. In fact, my university studies in sociology with an anthropological focus were significant for me. The passion for dance was always there, intertwined with a strong visual and partly critical-philosophical interest. When it came to making a choice, it was because emotionally it had become difficult to pursue both paths optimally. Once I received my diploma from the National Promotion Body “Movimento Danza” in Naples, I knew I wanted to follow this path, and it was time for me to leave and discover new realities. So, I started attending workshops and travelling to different destinations, trying to understand which places and dance practices resonated with me the most.

SP: When you left Italy to continue your studies at the Salzburg Experimental Academy of Dance, the first significant opportunities to work with internationally renowned choreographers also began. Could you tell us about the professionally and emotionally most important moments of your career during this period of your life? Moving abroad, did you encounter any significant differences in dance education and the perception of this profession, even from the audience’s perspective?

When I left Italy to pursue my studies at the Salzburg Experimental Academy of Dance, it also marked the beginning of my first important opportunities to work with internationally acclaimed choreographers. During this period of my career, there were several professionally and emotionally significant moments. Studying at SEAD felt like the most obvious and natural choice for me: when I managed to get in, I left everything behind. At that time, I was certain that I wanted to become a performer (I would have never imagined becoming a choreographer!), and I completely trusted the Academy’s training. In Salzburg, I mainly focused on studying, and towards the end of my training, I started professional encounters as a dancer. During this period, I studied extensively, worked as a performer (with Anton Lacky and Simone Forti, to mention some of the most significant experiences), and also observed many shows. Every year, there was the ImPulsTanz (Vienna International Dance Festival) in Vienna. Clearly, all these elements, intersecting with each other, had a strong impact on me: through experimentation, I became very aware of what I didn’t want to do, what approach to the stage and what use of the body interested me. If we consider that for my SEAD diploma solo, I had chosen a more theatrical than dance piece, with a strong visual approach, it was becoming clearer and clearer to me where I wanted to go.

When I was in Venice for a workshop with Yasmine Hugonnet, under the artistic direction of Virgilio Sieni at the Biennale Danza, a puzzle came together for me. The most valuable lesson I learned from working with Virgilio, beyond the choreographic approach, was the intellectual approach. Virgilio brought me back to the approach to text, how to read a text and bring it into the studio: he helped me reconcile my path as a dancer with my studies.

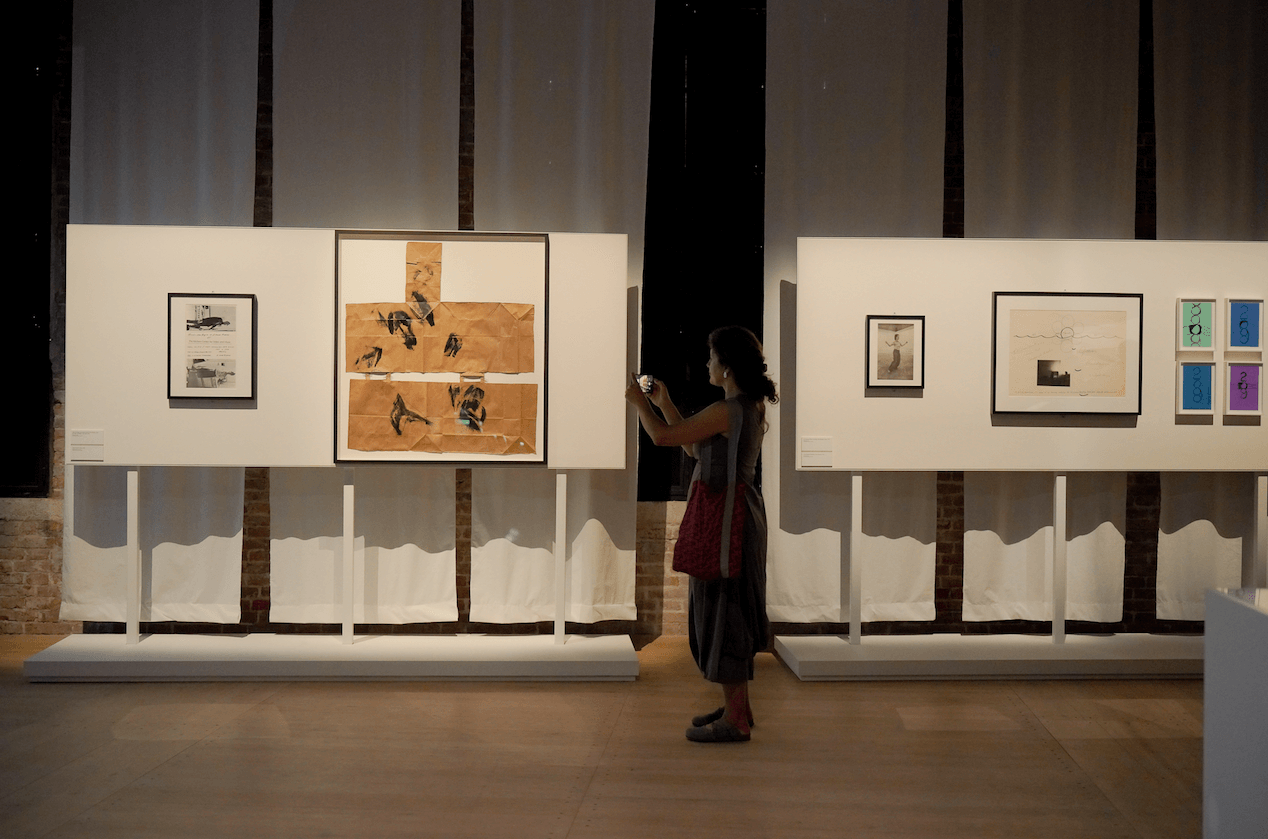

SP: In 2014, you meet Simone Forti, for whom you perform ‘Thinking With The Body: A Retrospective In Motion’ at the Museum De Moderne in Salzburg. Simone Forti is a prominent figure at this Biennale Danza 2023 – receiving the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement and having a retrospective exhibition dedicated to her, in collaboration with the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (MOCA). Could you tell us more about your encounter with Simone Forti, this particular experience, and how it has influenced your research on the body?

LC: My encounter with Simone Forti in 2014 was a profound and inspiring experience. Performing in ‘Thinking With The Body: A Retrospective In Motion’ at the Museum De Moderne in Salzburg was an incredible opportunity to work closely with such a legendary figure in the world of dance and performance art. Simone Forti’s artistic approach and deep understanding of the body as an expressive tool left a lasting impact on me.

At that time, I was occupied with work commitments with Anton Lacky, and despite having to miss a few days of Simone Forti’s two-week training, I was welcomed into the working group and had the great fortune of getting to know her personally. I remember the immense openness and willingness required to work with her – starting from the mechanism of neutrality but also playfulness in some of these works. These things may seem simple, but you have to completely surrender yourself and be fully present in what you are doing rather than focusing on the form of what you do. This is the most significant lesson I learned: transparency, availability, openness to look at yourself, the performer, in relation to space and others. When you are exposed, you can no longer hide behind movement: you are being influenced by the other and can only let it flow through you. This teaching has become an integral part of my work: to “expose” oneself completely in the act of subtraction, and even more so in vulnerability, makes you entirely transparent to the spectator’s gaze. This unconditional exposure is not easy to sustain; those who perform this way must practice every day to be so open.

Exposing oneself in this manner demands a deep level of vulnerability, and performers must practice daily to be able to present themselves with such openness. However, this level of transparency and vulnerability also allows for a unique connection with the audience, as it invites them to witness a genuine and unfiltered expression of the performer’s emotions and intentions. This approach to performance has become an essential aspect of my artistic practice, and it has influenced how I engage with movement and connect with both the space and the audience. It has taught me to embrace the authenticity of the moment and to let go of preconceived notions, allowing the dance to flow naturally and truthfully.

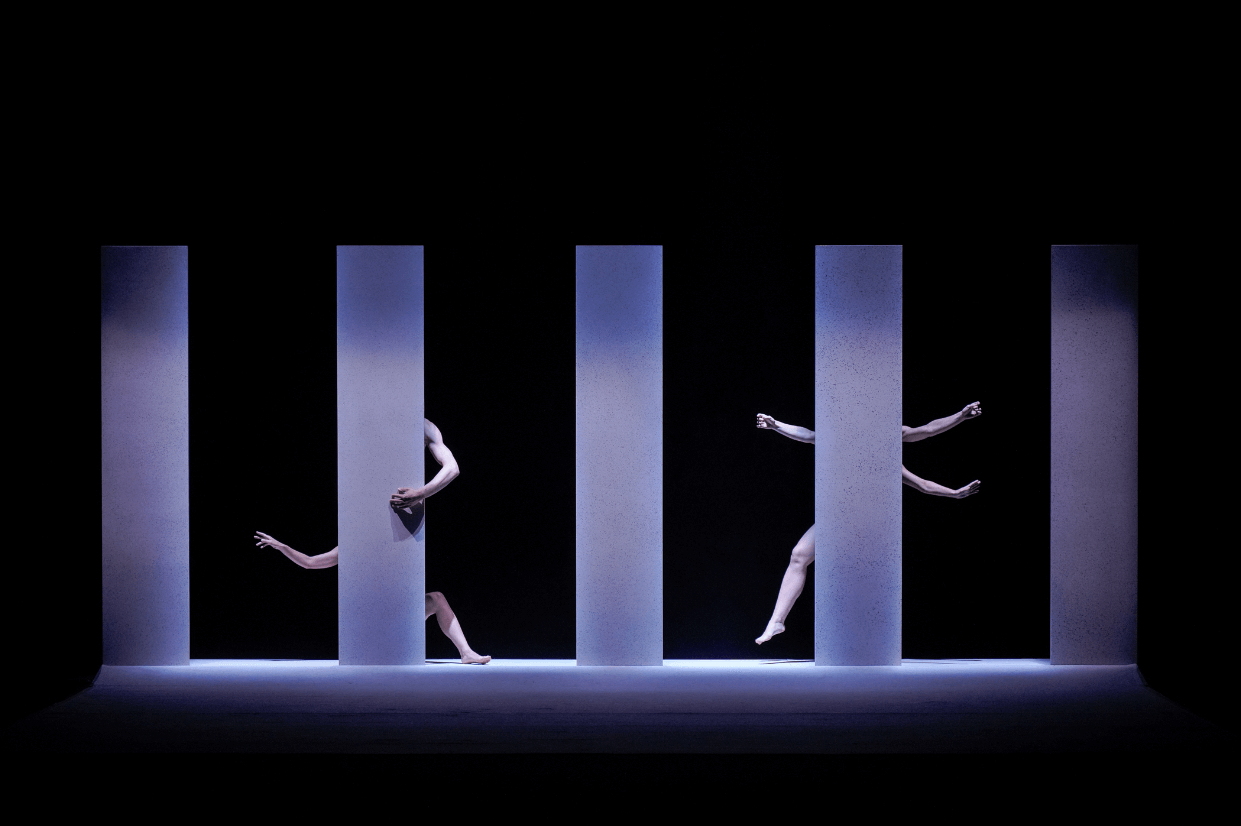

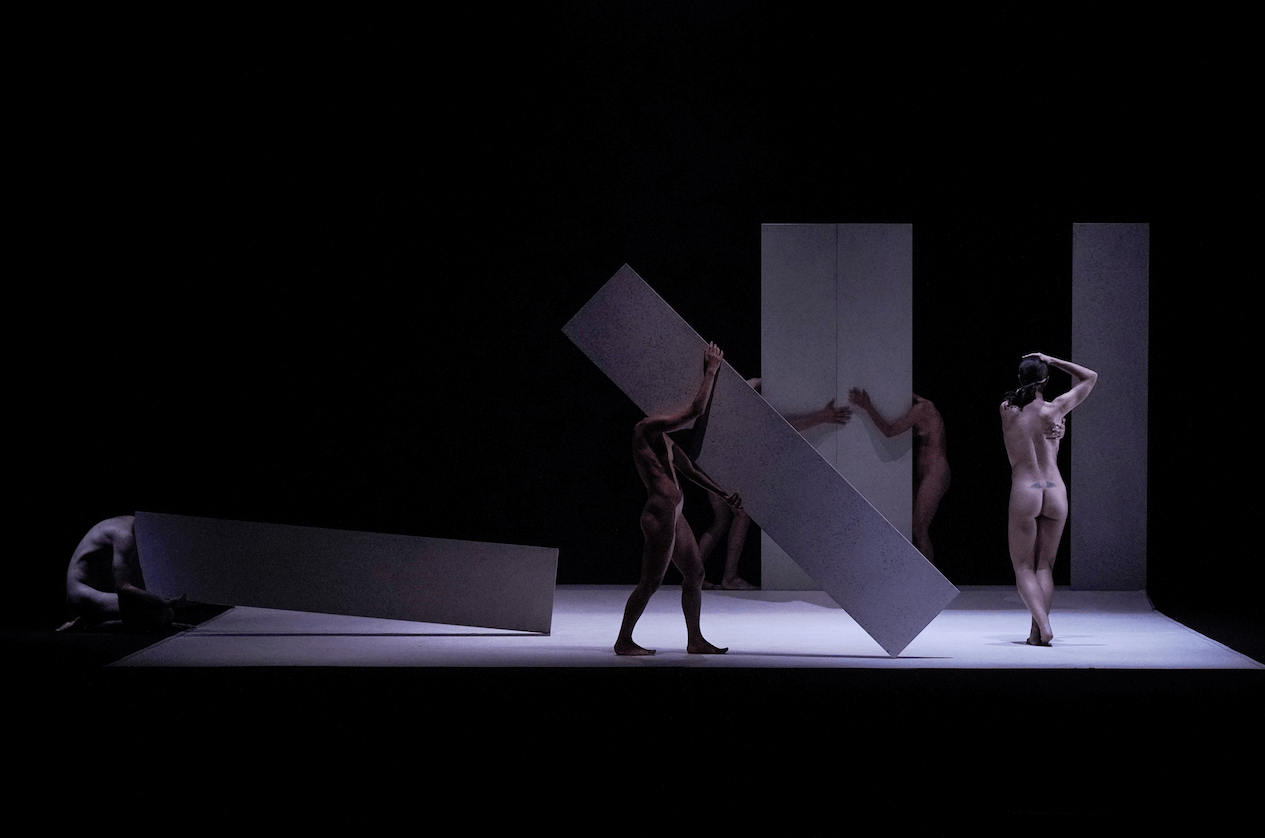

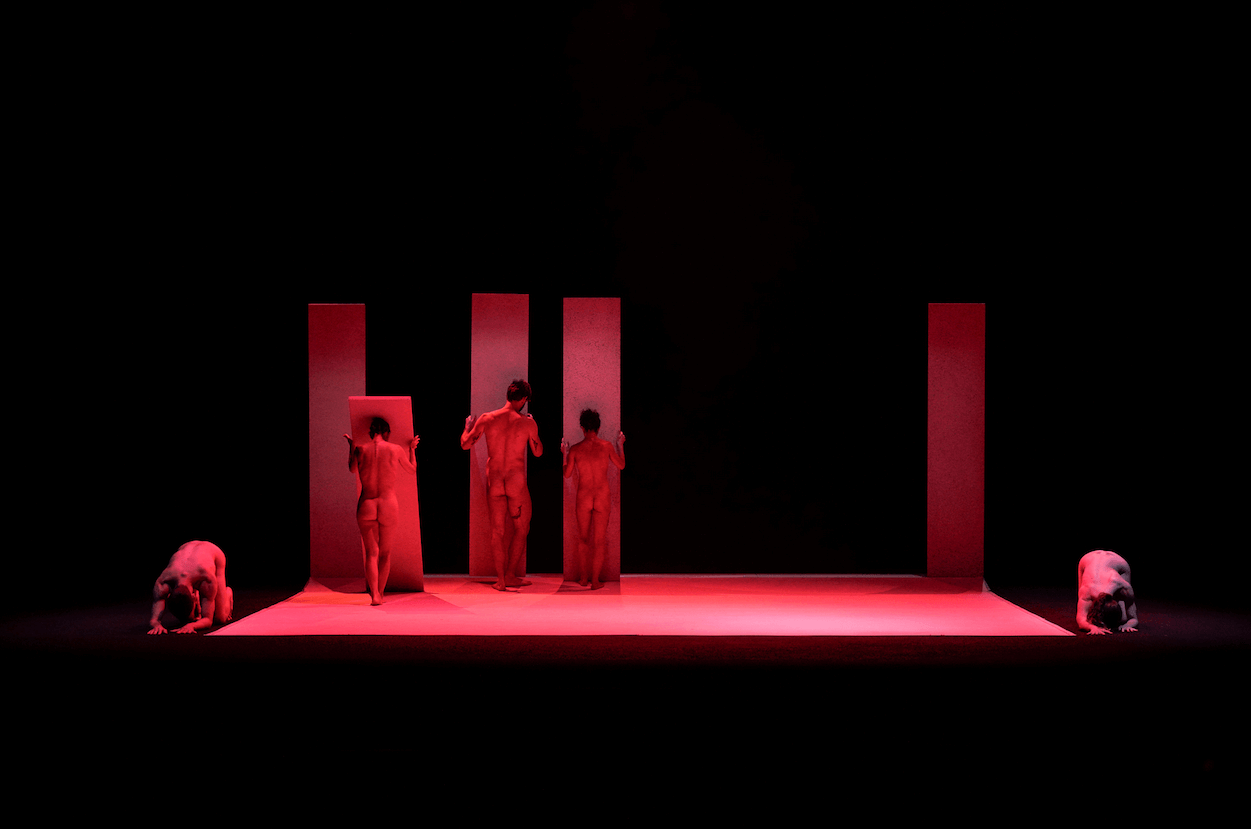

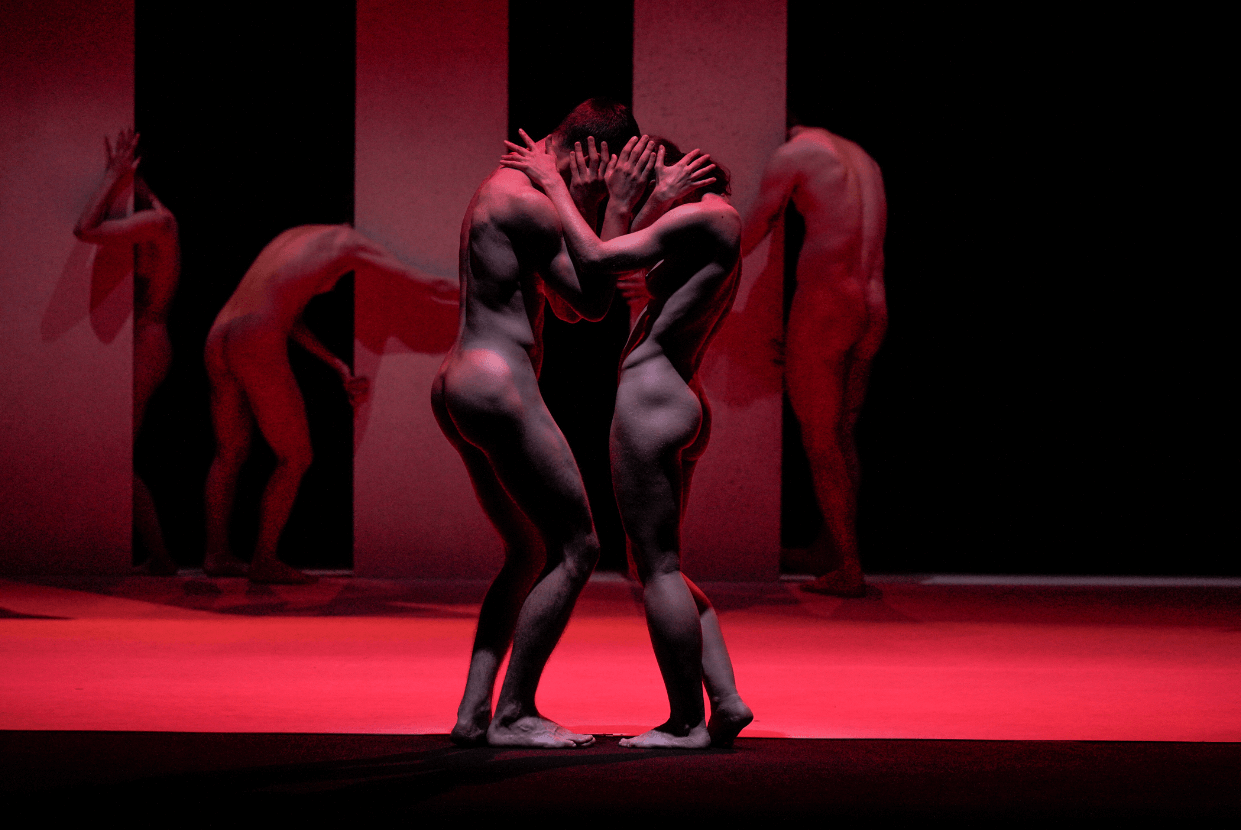

SP: From interpreter to choreographer. The Biennale Danza 2023 is the third edition directed by choreographer Wayne McGregor. You arrive in Venice as the winner, with the project “Vanishing Place” of the call for new choreographies aimed at artists under 35, which you brought to the stage of Teatro Piccolo Arsenale in its world premiere. With you are performers Marina Bertoni, Francesca La Stella, Ilaria Quaglia, Davide Tagliavini, Luca Zanni, accompanied by the music of Renato Grieco, set and light design by Giulia Broggi, and set design by Raffaele di Florio. Can you tell us about this project? How did the choreographic “writing” that led to the creation of “Vanishing Place” come about and develop?

LC: Through experimentation, I made everything that was close to me my own, experienced it, and absorbed it; on the other hand, I let go of what I did not identify with. I had always thought of myself as an interpreter until I reached a turning point: I felt that I had something of my own to express and that I wanted to put myself to the test, taking on both the risk and responsibility of this choice.

Years ago, I was offered the opportunity to create with objects, but I didn’t know what object I wanted to use. During a two-week workshop in Lazio, I found myself experimenting with boards found within the space. I wanted to add a new dimension to my body-oriented practice (based on observation, posture, breath study, etc.) by incorporating the relationship with objects. It can be said that this relationship was born by chance, but I immediately embraced the visual body-object connection that I witnessed in front of me with a profound exploration, also inspired by architecture and surrealistic photography. In those two weeks, the first materials emerged, and I decided to apply with them to the call for new choreographies aimed at artists under 35 for the Biennale Danza in Venice.

The entire journey from the moment we received the positive response for the production of the choreography at the Biennale Danza 2023 has been an enormous research endeavor. Much of this show is based on photographic imagery: we extensively studied the body’s relationship with the verticality of the object and, in dialogue with Raffaele di Florio, the proportion in relation to the scenic space’s architecture. With Giulia Broggi, I had numerous discussions about the light’s relationship with the space and the definition of the objects’ colors on stage. Finally, during the last staging in Naples, we worked extensively with the musician and composer Renato Grieco, who was with us in the studio and gifted me with valuable and unexpected insights.

The opportunity to present “Vanishing Place” at the Biennale Danza 2023, under the direction of Wayne McGregor, was both a thrilling and fulfilling experience.

SP: In “Vanishing Place” you look at the human body as a landscape and nudity as a necessary condition. You have said: “What is the body on stage? I wanted it to become something else, not just an anthropomorphic body, but a collective memory, a suggestion in the spectator, a landscape element in which everyone sees something.” I think this premise is fundamental to rehabilitate a concept of the body. Perhaps this is also why you see nudity as a necessary condition…?

LC: In “Vanishing Place,” the human body is viewed as more than just a physical form; it becomes a metaphorical landscape, carrying collective memories and evoking various emotions and interpretations in the spectator. This perspective allows for a more profound exploration of the body as an expressive medium beyond its conventional anthropomorphic representation. By presenting the body as a landscape, it invites the audience to engage with it on a deeper, more emotional level, prompting personal reflections and connections.

For me, nudity is primarily necessary at a compositional level concerning the posture I want to adopt as both an author and performer on stage. It is not obvious to have a clear awareness and perceptual image of our naked body – perhaps it is not essential for everyone, but I believe that for many people, it is genuinely important to approach this kind of perception, listening, and acceptance because it involves not only our own body but also that of the other. It is both a practice on stage and a practice for the observer, especially if on stage, I assume postures that allow for this perspective. This is related to composition. For example, I like to work with postures that hide the performer’s gaze: for me, it is a straightforward way to welcome the spectator’s gaze on the body. When we communicate with someone frontally, we are inclined to observe their face and attribute a personality to it; in this case, it’s about establishing deliberate, peaceful, poetic contact with the spectator by canceling the other’s gaze – it is a positive form of negation.

In this sense, the body becomes a landscape: you can rest your gaze on a body as you would on a landscape.

SP: In hearing these words, I thought of Gilles Deleuze’s “Abécédaire”. Speaking about desire, Deleuze states: “I don’t desire a woman, but I also desire the ‘landscape’ that is contained within that woman, a landscape that perhaps I don’t even know, but that I sense, and until I have developed this landscape, I will not be content, meaning my desire will not be fulfilled; it will remain unsatisfied.” Desire invites creative exploration of its object since the object is never already given or pre-existing; the indeterminacy of its object is the source of its creativity and freedom. Do you think dance can become an expression of creative and free rethinking? Do you think that through the performative act, the criteria of what is desirable today can be more critically reconsidered?

LC: Absolutely, dance has the potential to be a powerful medium for creative and free rethinking.

I don’t know why the body has become such an important theme for me. I do know that at a certain point in my career as a dancer, intertwined with the readings I continue to pursue, it led me to approach it more closely. Perhaps it was inevitable that I would go through dance to talk about this. For almost two years, I have been in the studio experimenting, observing, and removing layers. When you come from a background as a dancer, you find yourself in a condition where you rightly have to take in, assimilate, and make things your own – this is crucial during the period of study. Until the moment of “digestion” begins. During the time when I moved to Brussels after SEAD, I started a process of self-analysis, and there I began to deconstruct. I believe that a more freely creative rethinking of what constitutes us as bodies and as humans must go through a process of deconstruction.

As a dancer, the initial training involves absorbing and assimilating established techniques and styles, which is essential for growth and development. However, as one progresses in their artistic journey, there comes a time for introspection and questioning of established norms. This process of self-analysis and deconstruction allows for a deeper understanding of the body, movement, and their relationship to the self and the world.

SP: Sure, it’s about acknowledging what we are. Your choreographic research project is called “Genealogia.” Its main object of investigation reflects on the imaginary of the body: the different ways of thinking about the body and bodies today, considering their distances and proximities. As the title you chose for the project – “Genealogia” – aptly suggests, it encompasses both origin and birth, as well as difference or distance in origin. The distance and proximity of the body together: I am intertwined with others before being intertwined with my own body. “Genealogia” is a community project. Can you tell us more about it?

LC: One of the reasons why I felt a strong affinity with Virgilio Sieni, in addition to gestures and postures – themes that resonated deeply within me – was because of his work with communities. At a certain point within this journey, the film “Capri-Revolution” by Mario Martone also came into play, in which I participated. The film tells the story of a group of young artists who, on the eve of World War I, settle on the island of Capri and establish a commune. During this time, I worked with Raffaella Giordano, who was preparing us for movement. At that moment in my life – when I was going through this process of “deconstruction” as we previously mentioned – I found myself on the film set reading, and that’s where I began to conceive the “Genealogia” project.

“Genealogia” is a community project based on the sharing of thoughts and images: when I enter the studio, before starting the practices, we talk, read excerpts, and question things. For me, “Genealogia” is the synthesis of how we act based on a mental process; even the way we observe is a “product of.” If we want to question ourselves, we must first ask ourselves questions, and during the process, we try to bring these questions into the practices. The first significant milestone of “Genealogia” was in Rovereto during the Oriente Occidente festival. It was during the pandemic period: imagine talking about the body, distance, and proximity, about contact during a pandemic crisis. We had a tremendous opportunity to challenge everything we took for granted and to understand how much we need – in such an individualistic society – connection and community.

In “Genealogia,” the process involves a collective journey of self-inquiry and exploration, where participants engage in questioning, discussing, and creating together. The project seeks to create a space for shared experiences and reflections, exploring the interplay between individual identities and the collective body of society. By delving into themes of connection, distance, and community, “Genealogia” aims to challenge assumptions and societal norms, inviting us to reimagine our relationships with ourselves, others, and the world at large.

The genealogy of the body manifests through dialogue, the sharing of stories and personal experiences, involving both performers and the audience. This community approach creates a space for mutual exchange and learning, where individual identities and narratives intertwine to form a broader and more inclusive fabric.

SP: What are your plans for the upcoming months? Any events you can recommend to our readers?

LC: In August, we will be on stage with “Zoe” in Bassano del Grappa, as part of the OperaEstate festival and the section dedicated to contemporary languages called “B.Motion.” Then, at the end of August, we will be at the NID Platform 2023 in Cagliari. In winter, we have tour dates in Germany with both “Zoe” and “Vanishing Place,” and there are new projects on the horizon. So, stay tuned!